United Nations Education Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO):

https://en.unesco.org/indigenous-peoples/undrip

JOURNAL ENTRY

Vol 1. No. 1., p. 1-22, November 03, 2018.

People And Societal Integration Article!

The content may be utilized for educational purposes with suitable credit attributed to the author with site designation

The content may be utilized for educational purposes with suitable credit attributed to the author with site designation

Journal Research:

European Colonization And Intergenerational Traumatic Health Deficits Contributing To Gang Violence For Aboriginal Youths In Canada.

An Analysis Of Historical And Present-Day Government Social Policy To Determine What Works!

By: Joy Kissoon, B.S.Sc.-Criminal Justice, R.P.N., Artist

Author Reference:

- Public Health Agency of Canada, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada

- Government of Canada Publishing & Depository Services Directorate, Ottawa ON K1A 0S5

Correspondence: Joy Kissoon, B.S.Sc. – Criminal Justice, experienced nurse & artist; recent studies at Humber Lakeshore College Campus (Toronto, Canada). Mailing address: 515 Richmond Street, P.O. Box 54, Stn. B, London, Ontario, N6A 4V3, Email: health.care2010@yahoo.ca

Word Count For Main Text: 3,976

Analysis Consisting of: 1 Table, and 1 Figure

2

Abstract (246 words)

Introduction: European colonization is a period in Canadian history where British and French settlers began occupying territories, or Indigenous land in their quest for power overseas. The original inhabitants of Canada were First Nations, Metis and Inuit population; collectively referred to as Indigenous/Aboriginal peoples. Incidentally, colonization is proclaimed a causation of Intergenerational traumatic health deficits contributing to present-day gang violence for the Canadian Indigenous youth population. Statistics revealing Indigenous youths accounts for approximately 6% of the Canadian youth population. Yet, there are widespread media reports of Aboriginal youths’ gang violence in Canada.

Method: Theoretical, sociological perspectives chosen to deductively conceptualize, how Indigenous youths’ can benefit from social integration and life course interventions. Durkheim and Simpson, combined with Moffitt’s theoretical analysis utilized to determine what works to achieve social equilibrium for Indigenous youths. Thus, providing valuable theoretical insight into counteracting Intergenerational traumatic health deficits. Notable concern is trauma disseminated over the generational spectrum reflecting a ripple effect. Therefore, it is imperative to analyze legislative successes and failures such as: 1) The Indian Department, The British North American Act, The Royal Proclamation, The Indian Act, The Dominion Land Act, The Manitoba Act, Indian Residential Schools, Canadian Welfare System, and The Youth Criminal Justice Act (Y.C.J.A). 2) What works theoretically to counteract Intergenerational traumatic health deficits?

Concluding: Government legislative social policy interventions, exposing a rippling effect; proving European colonization and Intergenerational traumatic health deficits correlates to gang violence for Aboriginal youths in Canada.

Keywords: Indigenous, Aboriginal, Colonization, A Rippling Effect, Government Legislative Social Policies, Gang Violence, Youth Criminal Justice Act, Counteracting Intergenerational Trauma

Highlights (103 words)

- Intergenerational traumatic health deficits are experiences endured by Indigenous people during European colonization; that compromises future health status from generation to generation.

- Colonization and Indian Residential Schools (I.R.S) are determinants of health for Indigenous youths.

- Historic and present-day government legislative social policies (colonization) have a rippling effect on Indigenous youths in Canada.

- Intergenerational traumatic health deficits suffered by Canadian Indigenous youths are related to poor decision making, gang affiliation and gang violence.

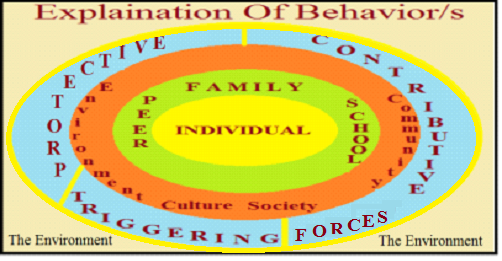

- Theoretically, environmental factors inclusive of individual-family-group-and-community are social determinants of health; contributing to wholistic wellness. Thus, social integration and life course development are significant for counteracting Intergenerational traumatic health deficits.

3

Introduction

Aboriginal youths are prone to Intergenerational traumatic health deficits stemming from European colonization (The Canadian Institute of Health Research, 2007). Thus, displaying inherited health deficits that impair Indigenous youths’ decision-making triggering gang violence in Canada (TCIoHR, 2007). Berube, (2015), explains Intergenerational trauma as a rippling effect disseminating from one generation to another via; parents, grandparents, and great grandparents. Each generation experiencing similar environmental, social, economic and health deficits. According to, Lewin (2017), the rippling effect is a social phenomenon impacting healthy outcomes for individuals where a persons’ environment, stress level, sleep pattern, exercise, nutrition, achievement, and daily activity are essential.

There are extensive literature reviews (Menzie, 2010; Paradies, 2016; TCIoHR, 2007), collaborating that Intergenerational traumatic health deficits are by-products of colonization. This literature study attempts to find historic legislations and trace the effect those legislations have on Intergenerational traumatic health deficits and gang violence among Indigenous youths in Canada. Theoretical analysis is essential to determine what works to counteract Intergenerational traumatic health deficits for Indigenous youths. Sociologist Durkheim and Simpson’s (1951), research provides an integrational perspective for theoretical behavior analysis. However, their work was limited, without actual statistical clarification, or generalization related to; age, sex, race, ethnicity, or social class. This literature review goes one step further by identifying the specific population, race, ethnicity and social class. Further, integrating Moffitt (1993), developmental analysis of behavior from childhood-to-adulthood too provide insight into positive socialization, and health benefits. The goal is nurturing social integration through life course development; with the expectation that positive socialization can counteract Intergenerational traumatic health deficits for Indigenous youths. Interestingly, Durkheim (1897/1951); White and Jodoin (2003), family and community bonds such as: school, peer groups, cultural affiliation and societal values are contributive forces essential to sustain protective, normative behaviors. Strong communities assist in elevating individuals’ self-esteem, thus avoiding triggers associated with antisocial behaviors (Paradies, 2016).

According to, Czyzewski (2011), “social determinants of health” are dependent on environmental factors that promote inclusiveness of individuals, families, and groups within communities. Whilst, Adelson (2005); Howell, Auger, Gomes, Brown, & Young Leon (2016), environmental health disparities are asymmetrical for Indigenous peoples; when compared to non-Indigenous Canadians. Environmental factors contributing to health disparity for Indigenous youths are: poor infrastructure, economic stagnation, inadequate housing, unemployment, poor earning potential and low academic integrity. Indigenous youths’ residing in physical environment riddled with systemic inequality and power imbalance, threatens health and socioeconomic stability (International Symposium on the Social Determinants of Indigenous Health, 2007). Likewise, during the ISotSDoIH (2007), for the Commission on Social Determinants of Health, evidence-based reporting distinguishes health as a human factor disproportional for the Indigenous population.

Study by Kong (2009), is symptomatic of vast over-representation and prisonization experienced by Aboriginal youths in the Canadian Criminal Justice System. Further, in 2007-and-2008, Kong (2009), reports Indigenous youths represent a mere six percent of the Canadian youth population. Yet, Indigenous youths in the criminal justice system represent: twenty-five percent in remand, thirty-three percent incarcerated, with twenty-one percent on probation. Similarly, statistics from the Department of Justice (2015a), revealing “incarceration rate for Aboriginal youths were 64.5 per 10,000 populations, while incarceration rate for non-Aboriginal youths were 8.2 per 10,000 populations (para. 2).” Likewise, the intensification of Indigenous youths’ custody figures for; Saskatchewan, Yukon, and Manitoba, were 16-to-30, times higher than any other provinces and territories in Canada.

4

Interestingly, Aboriginal youth’s gang violence is accentuated and sensationalized in Canadian media, Vice Staff (2014), labeling Winnipeg; “the murder capital of Canada (para. 1).” Likewise, studies by, Preston, Carr-Stewart and Bruno (2012), names Winnipeg the epicenter for Aboriginal youths’ gang violence. Nevertheless, Sawchuk (2017), list Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada as having a total of 13%, of the grand total of First Nations, Metis and Inuit population. Whilst, the entire Indigenous youth population makes up 6% of the total number of youths in Canada (Kong, 2009).

Locating Myself In This Research

Joy Kissoon

I am a first-generation migrant of minority Canadian status originally from Trinidad and Tobago (South America). I felt it was my duty and responsibility to assimilate, and the best way to do so was through education. I arrived in Canada with a college education from Trinidad and Tobago, with proficiency in; History, Biology, Commerce, English Language, and Art. In Canada, I began by enrolling in adult courses at the community high school, then free online courses on government of Canada website, while continuing with job training, and college courses. Later, I enrolled in prerequisite to nursing courses at Georgian College in Owen Sound, ON, then entered the Practical Nursing Program and registered with the College of Nurses in, 2003. Thereafter working in mental health and community nursing. My practice included working in shift and visiting nursing. My specialty has been pediatrics, geriatrics, out-patient, emergency and chronic care.

After arriving in Canada, I faced questions such as: Why Canada? Are the people in your country very poor? Why are you here? These questions can make an individual feel like a trespasser. However, I soon learned the original inhabitants of Canada are of Aboriginal and Indigenous backgrounds! Indigenous people, originally owned the land that migrants from many other nationality, and cultures now call home. I remain fascinated by the unique, vibrant culture of Aboriginal heritage. Having spent time in parts of Northern and Southern Ontario; I have seen the segregation and marginalization of First Nations people. Usually, Indigenous communities are found on the outskirts of small towns living in trailer parks communities with sub-standard housing, no electricity at times, or basic amenities for survival. Societal respect for Indigenous culture, heritage and peoples are low with reference to stigmatization of behaviors, and limited effort to truly comprehend the plight of Aboriginal peoples. Their communities rely on out-houses in times when the poorest most vulnerable in Canada enjoy adequate amenities; with heat, hydro, and toilet facility as basic necessities.

5

During my studies in Baccalaureate of Social Science – Criminal Justice at Humber Lakeshore College Campus, our courses were reflective of Indigenous history. I ceased every opportunity to do research papers and projects, even interviewing person of Indigenous heritage (Toronto City Hall, Ontario, Canada), to add to my knowledge of this vibrant culture. In third year the Honorable Judge Murray Sinclair, Chairman of The Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) visited Humber Lakeshore Campus with a presentation on; colonization, Intergenerational trauma suffered by Aboriginals, and specific goals of TRC. Only by learning, writing and presenting on Indigenous people’s heritage in a respectful way; can we hope to one day fully experience integration of Indigenous peoples in a whoistic society. A people, who to this day continues their battle to reinstate equality they lost some centuries ago. There are vast amounts of empirical studies regarding colonization and the ongoing plight of Indigenous peoples, it is essential to continue sharing knowledge learned about Indigenous heritage, and consequences of Intergenerational trauma with the public. We are different, yet we face the same struggles for survival in a society that continues to discriminate, weather intentional or unintentional; the outcome is the same.

Theoretical Analysis And Explanation Of Behavior

Empirical observations on theoretical sociological analysis provided by, Durkheim and Simpson (1951), describes individual integration as egoistic, whilst group/community integration referred to as altruistic, and lawful behaviors termed anomic. Positive social integration, group solidarity and law-abiding behaviors work to protect individuals from adverse risk factors. Social environmental integration is essential for maintaining lawful behaviors. However, too much, too little, or inadequate positive integration within groups (gangs); can trigger negative behaviors (Durkheim and Simpson, 1951).

Essentially, Durkheim’s (1897/1951), theory of social integration promotes cohesion in social groups. Whilst, Moffitt (1993), life course theory utilized to predict criminogenic factors related to life course outcomes. Life course theory describes two types of behaviors: 1) Adolescent-limited – described as normative due to immaturity, because the behavior is usually non-violent and does not persist into adulthood. 2) Life-course persistent antisocial stage – behaviors triggering criminogenic development during early childhood and continuing into adulthood.

Youths in unstable family and community environment tend to trigger risky behaviors; due to poor decision-making (White and Jodoin, 2003). Whilst, Moffitt (1993), “individuals develop neuropsychological risk for difficult temperament and behavioral problems; in the life-course persistent stage (p. 5).” Prevention is dependent on “underlying disposition change in manifestation when age and social circumstances alter opportunities (p. 6).”

6

Figure 1. Visual Representation Based On White And Jodoin (2003); Promising Strategies

According to White and Jodoin (2003), healthy behavior development can be achieved through environmental, social, cultural and societal integration. Family, peer, school, and community can be contributive forces that offer individual protection. Whilst, the environment created can be protective or risky; which essentially results in a society with strong structural values, or fragile, challenged and disabled (Durkheim & Simpson, 1951; Knoester & Haynie, 2005; Moffitt, 1993).

Intergenerational Traumatic Health Deficits

Interestingly, Paradies (2016); Totten (2009), The Canadian Free Press (2010); Vice Staff (2014), extensive literature analysis identifies Aboriginal youths’ as products of Intergenerational trauma. Acknowledging health deficits linked to social disintegration, economic instability, lack of positive family and group affiliations related to power imbalance from periods of colonization. Hence, triggering the development of self-harming behaviors due to poor decision-making skills, contributing to gang violence (Berube, 2015; Shulman and Tahirali, 2016).

Moreover, Shulman & Tahirali (2016), reported (in 2000), Aboriginal youths 15-to-24, were 5-to-6 times more likely to self-harm; causing death by suicide. Whilst, Indigenous youths’ (male) suicide rate were 102, per hundred thousand, higher than non-Indigenous youths. Czyzewski (2011), non-Aboriginals life-expectancy are 5-to-8 times better than that of Aboriginal peoples.

7

Furthermore, Corrado (2014); Johnson (2012); Paradies (2016); Public Safety Canada (2017a); Totten (2009), consequential Intergenerational trauma experienced consists off: land deprivation, economic stratification, loss of culturally traditional practices, loss of family through I.R.S., child abuse and neglect, physical-sexual and psychological abuse, perverse patterns of abuse both as victims and perpetrators, single parenting, inadequate bonding, poor health, low/no academic success, alcohol and drugs use, fetal alcohol spectrum disorder (F.A.S.D), poor decision-making, intense over-representation (prisonization), youths engaging in self-harm (internalized), as well as negative peer association linked to gang violence (externalized). These hydra-headed social triggers appears to have a rippling effect where Indigenous youths are susceptible to Intergenerational health deficits. Public Safety Canada, 2017a; Alfred, N.D; studies reveal colonization attributed to adverse health associated with Indigenous youths’ criminogenic behaviors.

Background – Gang Violence And Incarceration

Indigenous, or Aboriginal are used interchangeably in this research to represent the first people to occupy Canada; First Nations, Metis’ and Inuit peoples (White and Jodoin, 2003).

According to Menzie (2010); Paradies (2016), there are multiple evidence-based research linking Aboriginal Intergenerational traumatic health deficits to colonization. Similarly, studies by Grekul and LaBoucane-Benson (2008), contain testaments (ethnography) of Indigenous persons and law enforcement authority figures, experience within the culture of gang behavior and gang violence; verifying that colonization, racial discrimination, and deficiency of opportunity, contributes to Indigenous youths’ over-representation in the Criminal Justice System (Corrado, Kuehn & Margaritescu, 2014).

Present-day, Canadian Criminal Justice System (C.J.S) response to Aboriginal youths’ aggression, violence and crime (Grekul, et al., 2008; Jackson, 2015), are mass incarceration and over-representation. Studies, by Jackson (2015); Department of Justice (2015a), show disproportionately high rates of custody, remand and probation experienced by Aboriginal youths in Canada (Kong, 2009).

Further, Public Safety Canada, 2017a; Preston, et al. (2012), empirical studies indicate, Indigenous youths as young as eights years old start engaging in gang violence. However, the nominal age for gang entry is 12 years. Furthermore, Preston, et al. (2012), study reports in Alberta “approximately 44% of gang members are between the ages of 16 to 21 years old, the other 56% is 22 years old or older (p. 198).”

8

Purpose Of Researching Intergenerational Traumatic Health Deficits

This research is significant for analyzing contributive forces/triggers to Intergenerational trauma endured by Canadian Indigenous youths. It is essential to know how colonization impacts Intergenerational traumatic health deficits. Identifying social policies impacting Intergenerational traumatic health deficits can assist in determining successes and failures during European colonization. Further, documentation of Intergenerational trauma is necessary to verify the veracity of historic legislative interventions (colonization) on health deficits and behavioral triggers associated with Indigenous youths’ life outcomes. Similarly, counteracting Intergenerational traumatic health deficits by providing theoretical analysis is paramount. Durkheim and Simpson (1951); Moffitt (1993), focuses on integration and healthy child-youth-adult development in socially conducive environment. Therefore, this literature research analyzes legislations such as: 1) The Indian Department, The Indian Act, The British North American Act, The Royal Proclamation, The Dominion Land Act, The Manitoba Act, Canadian Welfare System, and The Youth Criminal Justice Act (Y.C.J.A). 2) What works theoretically to counteract Intergenerational traumatic health deficits?

Moreover, providing a guideline for meaningful government social change within Indigenous communities; may assist with managing health deficits triggering gang violence. Perhaps, assisting to plan strategies that work to counteract Intergenerational trauma, and communicate success. Treatment programs are great short-term interventions, but environmental stability, safety and security are equally important. Essentially, it is the responsibility of governments to assist with protective interventions for healthy child-youth-adult development; long-term.

Method

This literature review analyzed colonization (historic government social legislative interventions) (Table 1), and Intergenerational trauma to reveal contributing health deficits, triggering present-day gang violence for Aboriginal youths in Canada; disclosing a rippling effect. Theoretical analysis by Durkheim and Simpson (1951), linked with Moffitt (1993), provide interventions for what works to counteract Intergenerational traumatic health deficits (Figure 1). Evidence based literature utilized were: statistics, media reports, literature studies by persons of Aboriginal/Indigenous background (ethnography), government websites, including journal articles providing empirical observations of European colonization (legislative Acts), reports on Indian Residential Schools, the Canadian Welfare System, and the Criminal Justice System.

9

Goals of this study were to analyze colonial and present-day government legislative social policies, to determine the correlation to Intergenerational traumatic health deficits and Indigenous youths’ gang violence. Analyzing legislations such as: 1) The Indian Department, The British North American Act, The Royal Proclamation, The Indian Act, The Dominion Land Act, The Manitoba Act, Indian Residential Schools, Canadian Welfare System, and Y.C.J.A. 2) What works theoretically to counteract Intergenerational traumatic health deficits?

The population identified: Canadian Aboriginal youths of various descents, Metis, Inuit and First nations people. Thus, inclusive of Aboriginal youths, on and off reserves, status, or non-status, rural or urban, communities in Canada.

Results

Table 1. Canadian Government Interventions, Colonization, And Intergenerational Trauma Contributing To Health Deficits And Gang Violence

Government Social Legislation Policies or Interventions | Colonization | Intergenerational Traumatic Health Deficits (hydra Headed Social Triggers): The Rippling Effect | Successes and Failures |

The Indian Department (1755)(Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada, 2015) | Meant to protect Indigenous land & people; working to promote segregation & discrimination |

Contribute to loss of land, economic instability, loss of cultural identity & practices

| Failure to protect Indigenous land; contributing to mass deprivation, economic stagnation, poverty, displacement |

The Royal Proclamation (1763)(Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada, 2015) | All land to the West declared Indigenous. Later, with the introduction of more than 35 treaties, worked to rob Indigenous peoples of their land | Economic stratification, poverty, discrimination, stigmatization and marginalization | Success initially later turned to failure where Indigenous peoples striped of their lands rights and any control of their living situation |

The British North American Act (1867) (Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada, 2015) | Deprived Indians of basic human rights to territorial lands & control of Indigenous kids | Loss of cultural, social, family and community identity, loss of territorial lands | Nullification of cultural values, identities and social, cultural, spiritual, deprivation |

The Indian Act (1876) (Indigenous & Northern Affairs Canada, 2015; Chansonneuve, 2005); Joseph, 2013; Morden, 2016; Rennie, 2013) | Replacing the Indian Department and assuming control of aspects of Indigenous lifestyle & practices; Introduction of I.R.S. | Indians told what they can and cannot do, prohibiting aspects of cultural & social behavior | Legislative trap, annihilation of cultural values, language & practices for Indigenous youth community. Failing to protect, educate/assimilate |

The Dominion Land Act (1872)(Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada, 2015; Joseph, 2013) | Colonization where Eighty million hectares of Indigenous land in Western Canada transferred for colonist settlement | Legislation causing resource deprivation & economic hardship | Further loss of massive portions of territorial lands in Canada |

The Manitoba Act (1870)(Dangerfield, 2016; Joseph, 2013; Rennie, 2013) | Colonization allowing for land transfers to 7000 Metis kids; wrongfully issued to settlers | Lack of transfers led to more than 140 years of unrest & social deprivation | Failure stimulating discourse for more than a century; truce in 2016 between the Canadian government & Manitoba Métis Federation president |

Indian Residential Schools (I.R.S) (1892)(Bebrube, 2015; Chansonneuve 2005; Menzie 2010; Paradies, 2016; Totten, 2009; Woods, 2013)Closure of I.R.S. between 1969-and-1996(Bebrube, 2015; Chansonneuve, 2005; Johnson (2012), Menzie, 2010; Taiaiake, N.D) | Industrial boarding & I.R.S. (schools), homes for students, hostels, billets with a majority of day students, or a combination of anyColonization resulting in abuse & neglect of Indigenous kids – Public outcry led to closure of I.R.S. | I.R.S. separating Indigenous kids from their family values, cultural & spiritual heritage. Failure to educate, physical & psychological health deficitsPhysical & mental health deficits, sexual abuse & traumas, loss of environmental social family & community group integration, & stability | Failure to assimilate & educate. Worked to segregate, marginalize, annihilate, discriminate, fostering physical, sexual, emotional, spiritual, psychological & environmental traumaFailed to adequately integrate Indigenous kids into society. Resulting in transfers of children into the Canadian Welfare System where the cycle of abuse continues with ongoing attempts to assimilate by placing Indigenous kids in foster care with parents who cannot provide cultural values, practices and language association |

Canadian Welfare System (Government of Canada, 2018b; Johnson, 2012; Menzie, 2010; National Post, 2014) | Replaced I.R.S. Indigenous kids placed with Caucasian foster parents, identity nullification | Loss of stability within family & community triggering anxiety, depression, suicide, ill-health | Continue abuse & neglect of Indigenous children placed in homes of non-Indigenous parentage |

Youth Criminal Justice Act (2003)(Grekul, et al., 2008); Preston, et al., 2012; Statistics Canada, March 22, 2016a) | Overrepresentation & Prisonization learning coping strategies for survival – engaging in gang activity | Lack of love, belonging, safety, security, leniency, triggering suicide depression, & crime | Successful initially to reintegrate; then abuse of systemic authority contributing to crime & gang formation in Canadian urban area |

10

Discussion And Observation

The above table contains only a few documented legislations that dictated the path of colonization; along with present-day ramifications. The outline of this paper in no way expects to touch the actual depth of despair, annihilation and tragedy experienced by Indigenous peoples.

Each legislation listed above started out with the purpose of colonization, appearing to provide meaningful changes that could be supportive of Indigenous heritage. Only through time and differing perspectives each legislation were either changed or implemented in favor of European survival. As documented above, studies by, Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada (2015), reveals, The Indian Department (1755), failure to form alliances between European settlers and Aboriginal peoples. Instead of assimilating and integrating there were reports of fraudulent, abusive land transfers. Land treaties historically depriving Indigenous peoples of their livelihood, and economic integrity by confiscating land titles. Resulting in, centuries of Intergenerational traumatic health deficits, and unrest triggering present-day Aboriginal youths’ gang violence (Menzie, 2010; Paradies, 2016; Preston et al., 2012).

Similarly, The Royal Proclamation (1763), studied by Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada (2015), discloses “all land to the West were declared Indian Territories (Para. 5).” Later, new legislations and more than (35) land treaties witnessed re-transferring of land ownership to Europeans. Aboriginal peoples lost valuable economic resources, what appeared to be successful immediately turned into despair and trauma. Successful government legislative social policies provide for healthy integration rather than traumatic health deficits.

Incidentally, The British North American Act (BNA Act, 1867), worked to give Europeans authority over Indigenous children. Whilst, Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada (2015), were responsible for “Indians and Indian land,” a federal obligation to no avail (Para. 14). Similarly, The Indian Act (1876), described by Morden (2016), as authoritarian, regulating the lives of Indigenous peoples; a “legislative trap.” Further, The Dominion Land Act (1872), noted eighty million hectares of Indigenous land in Western Canada transferred for colonist settlement (Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada, 2015; Joseph, 2013). Thus, Aboriginal cultures experienced vulnerability, discrimination, and cultural annihilation, powerless to resist binding laws of Canada (Chansonneuve, 2005; Joseph, 2013; Rennie, 2013).

11

Dangerfield (2016); Joseph (2013), The Manitoba Act implemented in 1870, legislated land transfers of certificate or script land title to “7,000 children of the Red River Métis (Para. 1).” Likewise, Rennie (2013), a landmark ruling by the Supreme Court Of Canada, illustrating government failure to uphold the agreement put forward in the Manitoba Act (1870). The Supreme Court Of Canada, finally ruling in favor of Metis people after 140 years of unrest. Thus, the possibility of re-transferring approximately 5,565 acres, including all of Winnipeg; to Metis peoples (Joseph, 2013; Rennie, 2013). However, Dangerfield (2016), disclosing ”Manitoba Métis Federation president David Chartrand and Canada’s Indigenous Affairs Minister, Carolyn Bennett,” signed a truce agreement in Ottawa, which ends this land dispute dated since, 1870 (Para. 1). Mr. Chartrand revealing, Metis people simply wanted; acknowledgement, inclusion, integration, and respect not ownership of Winnipeg.

Indian Residential Schools (I.R.S.)

Colonist introduced Indian Residential Schools (I.R.S.) (1892), described by the Aboriginal Healing Foundation (2001:5), and cited by Chansonneuve (2005), “as industrial schools, boarding schools, homes for students, hostels, billets residential schools with a majority of day students, or a combination of any of the above (p. 33).” I.R.S., allowing the Crown to assume ownership of Native children, partnering with churches to; accommodate, educate and assimilate Indigenous youths (Woods, 2013). The United Church of Canada (1994), as cited by Menzie (2010), were involved in transfers of 100,000, or more Indigenous children to I.R.S.; between 1840-and-1983. Studies by Chansonneuve (2005), disclosing colonization and I.R.S., resulted in present day Intergenerational traumatic health deficits triggering present-day gang violence for Indigenous youths in Canada.

Likewise, the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples (1996:3), states the intervention of I.R.S. to address social problems of assimilation led to painful family segregation, language dissociation, economic stratification, cultural, emotion, and spiritual deprivation, along with sub-standard education. Bebrube, 2015; Chansonneuve, 2005; Menzie, 2010; Totten, 2009; Woods, 2013, summarize colonial legislative social policies contributing to health deficits triggering criminogenic behaviors for Aboriginal youths in Canada.

Due to widespread reports of abuse and oppression occurring at I.R.S. (Chansonneuve, 2005; Johnson, 2012; Taiaiake, N.D), between 1969-and-1996, the Canadian government closed all existing residential schools. Colonization and Intergenerational trauma contributing to health deficits triggering poor decision-making and gang violence for Indigenous youths (Menzie, 2010; Totten, 2009).

12

The Canadian Welfare System Replaced Indian Residential Schools

Research by the Government of Canada (2018b), confirms that more than, 50% of children in the Canadian Welfare System, or foster care (2016), are of Indigenous background. Whilst, “Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada (INAC), First Nations Child and Family Services (FNCFS) program funds prevention and protection services to support the safety and well-being of First Nations children and families on reserves (Para. 1).”

Finally, Siksika First Nations (1973), East of Calgary; followed by First Nation’s people (1990) (elders in Wabaseemoong); and Manitoba Aboriginal bands issued bans to prevent Children’s Aid Society, from entering reservation land and removing their children (National Post, 2014). Moffitt (1993); Durkheim and Simpson (1951), studies disclose family parentage and community integration is essential to the development of the child. Children forced to reside with non-Aboriginal parents, reporting devastating long-term cultural, and social health deficits (Johnson, 2012; Menzie, 2010; National Post, 2014). Empirical observations revealing colonial government social policy interventions correlated to present-day Intergenerational traumatic health deficits triggering criminogenic behaviors by Aboriginal youths in Canada.

Y.C.J.A. (2003), incarceration And Gang Violence

Department of Justice (2015a); Department of Justice (2016b), reports over-representation of Aboriginal youths in custody. Incidentally, The Young Offender Act (Y.O.A; 1984), introduced tough on crime initiative responsible for increasing incarceration rates among Indigenous youths. Further, Y.O.A was punitive lacking leniency related to Aboriginal youths’ prisonization. Therefore, prompting the introduction of the Youth Criminal Justice Act (Y.C.J.A., 2003), meant to promote leniency, integration and rehabilitation for non-violent youth offenders (Library of Parliament, 2012).

Friesen and O’Neil (2008), Aboriginal youth gangs were established in Canada since 1988, in Winnipeg with Indian Posse (IP). A prominent, high-ranking gang IP became contagious for Indigenous youths faced with economic deprivation spreading to; Saskatoon, Edmonton and the prairies. Soon, Manitoba had similar development of gang life known as; Manitoba warriors which expanded to Saskatchewan and Alberta (warriors). In response to IP and Manitoba warriors, Aboriginal youths formed a third gang during incarceration to protect themselves from attack; known as Native Syndicate. This gang developed from the inmate population through the process of prisonization; where inmates learn survival skills that are crime oriented (Public Safety Canada, 2017a).

Based on research by Preston, et al., 2012, female gang members also exist, but are small in numbers example; British Columbia (12%), Manitoba (10%), and Saskatchewan (9%).

13

Limitations

This study focuses on analysis of historic and present-day legislative social policy interventions correlating to Intergenerational traumatic health deficits and Aboriginal youths’ gang violence; identifying the rippling effect. However, this study theoretical perspective relies on sociological environmental challenges and does not consider data related to genetic correlation for Intergenerational traumatic health deficits.

Social changes implemented by the current Liberal government, appears to reflect positively on short and long-term environmental goals. However, it will take another 5-10 years before any substantial changes can be accounted for; when analyzing integration, lawful behavior, and developmental maturity of child-and-youth projection. Qualitative research to examine the effect of government legislative interventions; could provide insight into healthy outcomes for Indigenous communities. Similarly, accountability of government expenditure and promotion of Indigenous self-government need constant review; to determine long-term successes and failures.

What Works To Counteract-Intergenerational Traumatic Health Deficits

According to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) of Canada (N.D); Alfred (N.D), Judge Murray Sinclair (Persons of Indigenous heritage) founder of the TRC stresses the plight of Aboriginal peoples spanning over 7 generations (the rippling effect). Life course theory is specific to growth and development that encourages protective environmental integration; focusing on child-youth-family-group-and-community from a wholistic perspective (Durkheim et al., 1951; Knoester & Haynie, 2005; Moffitt, 1993).

14

Government of Canada (March 23, 2018d), announced plans to replace INAC with “Indigenous Services Canada (ISC) and Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada (CIRNAC);” working to alleviate socioeconomic stagnation plaguing Indigenous youths and manage health deficits.

Government of Canada, February 12, 2018a, improve environmental protection by; introducing clean water that ended eleven, Slate Falls Nations, drinking water advisory. The water treatment plant was funded by ISC ($11.6 million) and serves to promote healthy worry-free water availability for the entire community. Installation to fire hydrants and pump included to promote community fire protection. ISC, is working proactively with Aboriginal reserves to permanently end all water advisories (long-term) by March 2021. Providing reliable “wastewater infrastructure and ensuring proper operation and maintenance (Para. 4).” The 2016, fiscal budget allocated $1.8 billion (over 5 years), for reserves to ensure proper drinking water, wastewater infrastructure, and training of personal for water system operation and maintenance.

Further, Government of Canada (February 09, 2018c), Batchewana First Nation community received funding ($134,400.), “for IT modernization through its Community Opportunity Readiness Program, providing automation for current and future business (Para. 4 & 6).”

Government of Canada (2018e), passed another $1.94 billion (2016–2017) in funding through ISC, (over 5 years) for development of elementary and secondary education for First Nations children and youths. Moffitt (1993), a change in social integration could alter opportunity to engage in crime for Aboriginal youths; the rippling effect. Treatment is necessary to prevent health deficits, suicide and other criminogenic antisocial behaviors.

Best practice includes, but is not limited to (White and Jodoin, 2003):

Youth groups/councils, community individuals and caregivers, band and tribal councils, tribal administrators, Elders, agencies and organizations serving youth and families, mental health workers, addiction counselors, health nurses, social workers, government decision-makers, school administrators and teachers, community organizations and agencies, justice system, and police/RCMP members (p.3).

These methods of treatment emphasize intradisciplinary, interdisciplinary and multidisciplinary approaches to health care. Healthy individual Durkheim & Simpson (1951); Moffitt (1993), contributes to healthy child parenting skills, resulting in better decision-making, positive social integration and law-abiding skills to counteract Intergenerational trauma.

15

Study by Bonta, Wallace-Capretta, Rooney and Mcanoy (2002), focuses on harm reparation, integration and diversion from prison culture with restorative justice application to decrease recidivism. Determining, harm reparation is a key determinant in solution-based initiatives.

Likewise, Durkheim and Simpson (1951), explains an individual lacking positive social integration is more prone to developing antisocial behaviors. Hence more likely to engage in deviance, crime and gang violence.

Conclusion

The above literature research discussions focused on European colonization and Intergenerational traumatic health deficits triggering gang violence for Aboriginal youths in Canada. Concluding that European colonization and Intergenerational traumatic health deficits, are correlated to Indigenous youths’ gang violence in Canada; not necessarily a causation. Of the modest six percent of Indigenous youths in Canada not all youths of this ethnicity will engage in gang activity. However, the number of Aboriginal youths incarcerated is phenomenally high, and is not consistent with population analysis. More focus must be placed on authority figures representative of the Criminal Justice System, and practices of leniency towards Indigenous youths in Canada. Likewise, Canadian media over-emphasizing and sensationalizing Indigenous gang violence tends to also contribute to a ripple effect in the criminal justice system. Analysis of colonization (historical government legislative social policy interventions) reveals Intergenerational traumatic health deficits correlates to criminogenic behaviors (the rippling effect). The Indigenous youth population is experiencing disintegration with socio-economic hardships plaguing health outcomes. This literature review confirms Intergenerational trauma is a chronic debilitating health concern contributing to hydra-headed social triggers. These results are generalizable among Indigenous youths; First Nations, Innuit, and Metis communities.

16

Colonization witnessed the intervention of government legislative social policies, that were later abandoned and, or replaced because of long-term failures. Whilst, 21st. century European descendants continue blaming, discriminating, and promoting disintegration to compensate for historic harms.

Goals of providing theoretical analysis are to weed out a pattern for counteracting Intergenerational traumatic health deficits, correlating to Indigenous youths’ gang violence. Hence, determining government social policies can make the difference between positive, or negative environmental development. The Canadian Criminal Justice System needs to focus more on Indigenous rehabilitation and reconciliation rather than incarceration.

Whilst, theoretical perspective by sociologist Durkheim, focuses on long-term government social integration, combined with Moffitt’s life course theory highlighting relevance of child-youth-family-group-community integration to manage criminogenic behaviors. Evidence-based observations support compatibility of Durkheim and Moffitt’s theoretical analysis for the Indigenous youth population. Positive social integrated attachments, in childhood development promote healthy outcomes for protecting Indigenous youths.

Best practices identified to combat present-day Indigenous youths’ gang violence are: positive family and parenting skills, inclusion, integration, economic stability, education, employment, housing, with successful government legislative social policies. Whilst, positive child-youth, family, group-community solidarity, warmth, love and belonging, autonomy, restorative justice, community programs, re-establishing cultural identity with pride, and proactive law, or leniency replacing reactive interventions, contribute to strong vital Indigenous communities.

17

Acknowledgement

I would like to take this opportunity to thank the new Liberal Government of Canada and the Honorable Prime Minister Justin Trudeau for their dedication to Indigenous relations; making it possible for Indigenous youths to receive resources for meaningful social interventions. Particular thanks to Dr. Taiaiake Alfred, for his decades of public and private works revealing the true plight of Indigenous Peoples. Many thanks to Humber Lakeshore Library Staff ,who provided much of the resources for this research. Last, but not least thanks to Criminology professors at Humber Lakeshore Campus.

Conflict of interest

This is an independent research study, there are no conflict of interest.

References

1. Adelson, N. (2015). The Embodiment Of Inequality: Health Disparities In Aboriginal Canada. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 96, S45-S61

2. Alfred, T. (N.D) Canadian Colonialism. http://www3.nfb.ca/enclasse/doclens/visau/index.php? mode=theme&language=english&theme=30662&film=&excerpt=&submode=about&expmode=1

3. Berube, K. (2015). Intergenerational Trauma Of First Nations Still Runs Deep. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/life/health- and-fitness/health-advisor/the-intergenerational-trauma-of-first-nations-still-runs-deep/article23013789/

4. Bonta, J., Wallace-Capretta, S., Rooney, J., & Mcanoy, K. (2002). An Outcome Evaluation Of A Restorative Justice Alternative To Incarceration. Contemporary Justice Review, 5(4), 319-338. 10.1080/10282580214772

5. Canadian Institute Of Health Research (2007). Fetal Alcohol Syndronme And Fetal Alcohol Effect (archived). http://www.cihr-lrsc.gc.ca/e/4297.html

6. Chansonneuve, D. (2005). Reclaiming Connections: Understanding Residential School Trauma Among Aboriginal People. http://www.ahf.ca/downloads/healing-trauma-web-eng.pdf

7. Corrado, R. R., Kuehn, S., & Margaritescu, I. (2014). Policy Issues Regarding The Overrepresentation Of Incarcerated Aboriginal Young Offenders In A Canadian Context. Youth Justice, 14(1), 40-62. 10.1177/1473225413520361

8. Czyzewski, K. (2011). Colonialism As A Broader Social Determinant Of Health. The International Indigenous Policy Journal, 2(1). https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/iipj/vol2/1/5/

18

9. Dangerfield K. (2016). Canada, Manitoba Metis Sign Deal To End Land Dispute From 1870. https://globalnews.ca/news/3069867/canada-manitoba- metis-sign-deal-to-end-land-dispute-from-1870/

10. Department Of Justice (2015a). A One-Day Snapshot Of Aboriginal Youth In Custody Across Canada: Phase II. http://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/rp-pr/cj-jp/yj-jj/yj2/p3.html#p3_1

11. Department Of Justice (2016b). The Evolution Of Juvenile Justice In Canada. http://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/rp-pr/csj-sjc/ilp- pji/jj2-jm2/sec03.html

12. Durkheim, E. (1897/1951). Suicide. New York: Free Press

13. Durkheim, E., & Simpson, G. (1951). Suicide: A study In sociology. New York: Free Press

14. Friesen, J.T & O’Neill, K. (2008, May 9). Armed Posses Spreading Violence Across The Prairie Communities. The Globe And Mail, p. A16

15. Government Of Canada (February 12, 2018a). Federal Government And Slate Falls Nation Mark Significant Milestone As Ontario First Nation Lifts Eleven Long-Term Drinking Water Advisories. https://www.canada.ca/en/indigenous- servicescanada/news/2018/02/federal_governmentandslatefallsnationmark significantmilestoneaso.html

19

16. Government Of Canada (2018b). First Nations Child And Family Services. https://www.aadnc- aandc.gc.ca/eng/1100100035204/1100100035205

17. Government Of Canada (February 09, 2018c). Government Of Canada Supporting The Modernization Of Batchewana First Nation’s Information Technology Infrastructure. htps://www.canada.ca/en/indigenous-services-canada/news/2018/02/ government_of_canadasupportingthemodernization ofbatchewanafirstn.html

18. Government Of Canada (March 23, 2018d). Indigenous Services Canada. https://www.canada.ca/en/indigenous-services- canada.html

19. Government Of Canada (2018e). Kindergartner To Grade 12 Education. https://www.aadnc- aandc.gc.ca/eng/1100100033676/1100100033677

20. Grekul, J. M., & LaBoucane-Benson, P. (2008). Aboriginal Gangs And Their (dis)Placement: Contextualizing Recruitment, Membership, And Status. Canadian Journal Of Criminology And Criminal Justice, 50(1), 59-82. 10.3138/cjccj.50.1.59

21. Howell, T., Auger, M., Gomes, T., Brown, F. L., & Young Leon, A. (2016). Sharing Our Wisdom: A holistic Aboriginal Health Initiative. International Journal Of Indigenous Health, 11(1), 111. 10.18357/ijih111201616015

22. Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada (2015). A History Of Northern Affairs Canada. https://www.aadnc- aandc.gc.ca/eng/1314977281262/1314977321448

23. International Symposium On The Social Determinants Of Indigenous Health (2007). Social Determinants And Indigenous Health: The International Experience And Its Policy Implications. Adelaide, Report For The Commission On Social Determinants Of Health.

24. Jackson, N. (2015). Aboriginal Youth Overrepresentation In Canadian Correctional Services: Judicial And Non-Judicial Actors And Influence. https://www.albertalawreview.com/index.php/ALR/article/viewFile/293/291

25. Johnson S. (Mukwa Musayett) (2012). Failing To Protect And Provide In The “Best Place on Earth”: Can Indigenous Children In Canada Be Safe If Their Mothers Aren’t? https://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/obj/thesescanada/vol2/OSUL/TC-OSUL-1980.pdf

20

26. Joseph, B. (2018). The Script – What Is It And How Did It Affect Metis History. https://www.ictinc.ca/blog/the-scrip-how- did-the-scrip-policy-affect-metis-history

27. Knoester, C., & Haynie, D. L. (2005). Community Context, Social Integration Into Family, And Youth Violence. Journal Of Marriage And Family, 67(3), 767-780.doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2005.00168.x

29. Lewin, E. (2017). Using The “Ripple Effect” To Achieve Health Goals. https://www.smh.com.au/lifestyle/health-and- wellness/using-the-ripple-effect-to-achiev e-health-goals-20170612-gwp6tn.html

30. Library Of Parliament (2012). Current Publications: Social Affairs And Publications. https://lop.parl.ca/Content/LOP/ResearchPublications/2008-23-e.htm#a6

31. Menzie, P. (2010). Intergenerational Trauma From A Mental Health Perspective. Native Social Work Journal. https://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/obj/thesescanada/vol2/OSUL/TC-OSUL-384.PDF

32. Moffitt, T. E. (1993). Adolescence-limited And Life-course-persistent Antisocial Behavior: A Developmental Taxonomy. Psychological Review, 100(4), 674-701.doi:10.1037/0033-295X.100.4.674

33. Morden, M. (2016). Theorizing The Resilience Of The Indian Act: Indian Act Resilience.Canadian Public Administration, 59(1), 113-133. 10.1111/capa.12162

34. National Post (2014). A Lost Tribe’: Child Welfare System Accused Of Repeating Residential School History. http://nationalpost.com/news/canada/a-lost-tribe-child-welfare-system-accused-of-repea ting-residential-school-history- sapping-aboriginal-kids-from-their-homes

35. Paradies, Y. (2016). Colonisation, Racism And Indigenous Health. Journal Of Population Research, 33(1), 83-96. 10.1007/s12546-016-9159-y

36. Preston, J. P., Carr-Stewart, S., & Bruno, C. (2012). The Growth Of Aboriginal Youth Gangs in Canada. Canadian Journal Of Native Studies, 32(2), 193.

37. Public Safety Canada (2017a). Youth Gangs In Canada: A Review Of Current Topic And Issues. https://www.publicsafety.gc.ca/cnt/rsrcs/pblctns/2017-r001/index-en.aspx#a09

38. Public Safety Canada (2018b). Youth Gangs In Canada: What Do We Know? https://www/publicsafety.gc.ca/cnt.rsrcs/pblctns/gngs-cnd/index-en.aspx

21

39. Rennie, S (2013). Supreme Court Sides With Metis In Historic Land Claim Dispute. https://www.thestar.com/news/canada/2013/03/08/supreme_court_sides_with_metis_in _historic_land_claim.html

40. Royal Commission On Aboriginal Peoples (1996). Volume 3: Gathering Strength.Ottawa: Supply and Services Canada

41. Sawchuk J. (2017). Social Conditions Of Indigenous Peoples In Canada. http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/native-people-social-conditions/

42. Shulman, M., & Tahirali, J. (2016). Suicide Among Canada’s First Nations: Key Numbers. http://www.ctvnews.ca/health/suicide-among-canada-s-first-nations-key-numbers-1.2854899

43. Statistics Canada (March 22, 2016a). Youth Correctional Statistics In Canada, 2014/2015. https://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/85- 002-x/2016001/article/14317-eng.htm

44. Statistic Canada (2012b). Youth Correctional Statistic In Canada, 2010/2011. https://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/85-002- x/2012001/article/11716-eng.htm#a4

45. The Canadian Press (2010). Native Gangs Spreading Across Canada. http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/manitoba/native- gangs-spreading-across-canada-.1873168

46. Totten, M. (2009). Aboriginal Youth And Violent Gang Involvement In Canada: Quality Prevention Strategies. http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download? doi=10.1.1.543.9472&rep=rep1&type=pdf168

22

47. Truth And Reconciliation Commission Of Canada (N.D). Truth & Reconciliation. http://www.trc.ca/websites/trcinstitution/index.php?p=10

48. Vice Staff (2014). The Aboriginal Gangs Of Winnipeg. https://www.vice.com/en_ca/article/4w74eq/the-aboriginal-gangs-of- winnipeg-141

49. White J., & Jodoin N. (2003). Aboriginal Youth: A Manual Of Promising Suicide Prevention Strategies. https://www.cmho.org/documents/res-prom-stat-en.pdf

Inspiration & Direction

With any research one needs inspiration and direction, so I tunneled through seeking “The Indigenous Perspective.”

RE: One of the individuals that inspired me during my research..and this is after reading on and on —– an abundance of journal articles to compile the above thesis generated research during my forth year undergrad study in B.S. Sc.-Criminal Justice.

This morning (November 01, 2018), I did a google search and noted that Dr. Taiaiake Alfred is a professor at the University of Victoria in Political Science..and or Indigenous governance, I went further to read student's feedback..and feel the need to say thanks to Professor Taiaiake Alfred for his work in humanity and human relations.

Dr. Alfred’s piece gave me direction even though it was not dated….…and we were urged to stay away from references that had no date, but because of the impact the article held for me when reading the writings of a person of Indigenous heritage…I felt this was enough to hold integrity on my reference list. I remember going back to the article several times and reading it again and again to get direction..how did I want this paper to flow what is the mood..I did not want to be overly blunt about the role of governments, because this research is based on historic revelation. Hence, I sort peace and unity by pulling the 2 pieces together..Indigenous survival and government intervention.

The short piece simply written, clearly one of Dr. Alfred’s earlier works, a little blunt, but understandably so!….What really got my attention was Professor Taiaiake Alfred's mention of Indigenous coping strategies due to traumas of colonization..mere survival techniques…that the uninformed uses to stigmatize Aboriginals. My goals in this research were to reach crossroads where there are possibilities of recording findings, but also producing equally attributed empirical data on social circumstances, based on theoretical analysis supported by Intergenerational trauma.

Please see other works and links by Dr. Taiaiake Alfred @:

-- https://www.google.ca/search?source=hp&ei=H8KHXOqDL8uZjwT1lbnwAw&q=taiaiake+alfred+youtube&oq=taiaiake+alfred%3B+you&gs_l=psy-ab.1.0.0i22i30.2465.14689..16629...0.0..0.148.2114.10j10......0....1..gws-wiz.....0..0i131j0j0i10.HOclGH-3_WM

-- https://taiaiake.net/

-- https://www.google.ca/search?source=hp&ei=H8KHXOqDL8uZjwT1lbnwAw&q=taiaiake+alfred+youtube&oq=taiaiake+alfred%3B+you&gs_l=psy-ab.1.0.0i22i30.2465.14689..16629...0.0..0.148.2114.10j10......0....1..gws-wiz.....0..0i131j0j0i10.HOclGH-3_WM

-- https://taiaiake.net/

In life there are many crossroads, but as humans we must continue to strive for: equality, freedom of choice, justice, fairness, peace and harmony. Always abiding by Natural Law Theory Principles/God's Law encompassing infinite legal methods of living without inflicting harm on each other..

The 7 Hermetic Principles for Self-Mastery - The Teachings of Hermes-Thoth

By: Gary Lite (Published October 03, 2018)

No comments:

Post a Comment